Formation of the Santa Claus Image

20th Dec 2022

As Christmas approaches, BlytheRay studies the formation of the Santa Claus image – a story that intersects with religion, folklore, art, poetry, propaganda, and Coca Cola advertising campaigns.

The vast expanse of Santa Claus’ global reach has enabled depictions of his image to divert in multiple directions throughout history.

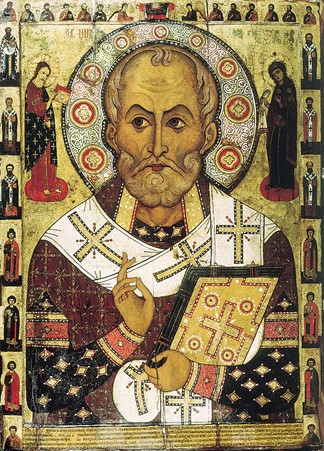

The origins of Santa Claus revert back to one historical figure; St. Nicholas, a 4th-century Greek saint who had a reputation for gift-giving and is apotheosised as the patron saint for children. Understandably, this drew an association between St. Nicholas and material generosity – especially to the world’s youth – which has remained one of the fundamental aspects of his image as it’s transcended borders and interacted with national cultures.

The name ‘Santa Claus’ derives from the informal Dutch name for St. Nicholas, Sinterklaas. Sinterklaas was often depicted carrying a staff and riding above rooftops on a huge white horse whilst mischievous helpers listened at chimneys to evaluate which children were well behaved.

In English folklore, Father Christmas overlapped with characteristics of Santa Claus but more heavily represented the spirit of good cheer at Christmas, and not gift-giving.

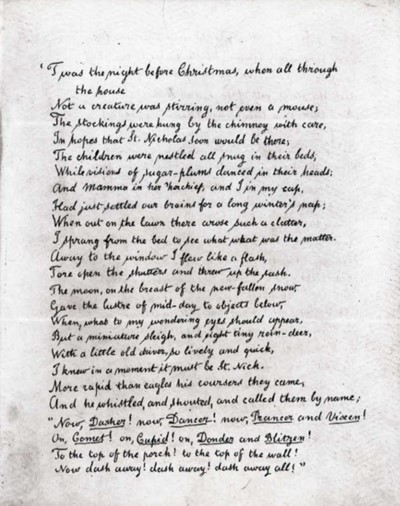

Heavy Dutch settlement on the east coast of America in the early 19th century was the catalyst for the Americanised image of Santa Claus. When St. Nicholas was pronounced patron saint of New York City in 1804, the New York Historical Society – and artist Alexander Anderson – promoted an image of a religious figure that deposited gifts in fireside stockings. In Knickerbocker’s History of New York, Washington Irving described St. Nicholas as ‘jolly’ figure who flew in a sleigh pulled by reindeer and delivered presents via chimneys. This was developed further in Clement Moore’s famous 1822 poem A Visit from St. Nicholas, known better as The Night Before Christmas.

As time progressed, more features were added to the Santa Claus image. Thomas Nast’s cartoons for Harper’s Weekly proliferated popular culture by wholly crafting a scene around Santa; the reindeer, sleigh, naughty and nice list, and workshop all adorned the background of his illustrations. However, the notion of Santa wearing a red suit was not yet concrete.

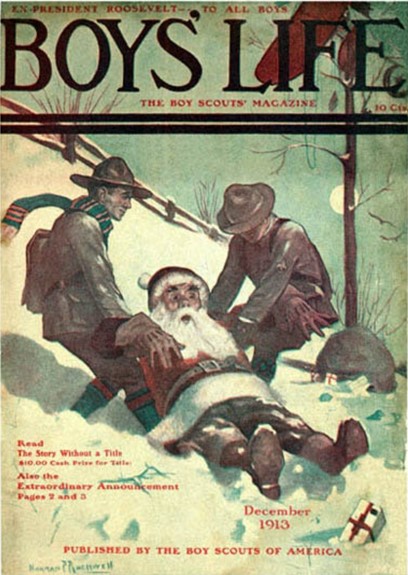

Legendary illustrator Norman Rockwell, whose depictions of Santa Claus were annually featured in the Saturday Evening Post during the early-1900s, portrayed him in an entirely human and naturalistic way, and opted for red as the colour of his clothing.

In propaganda posters from the First World War, the red of Santa’s suit was present, demonstrating that this depiction had extended beyond use in popular media.

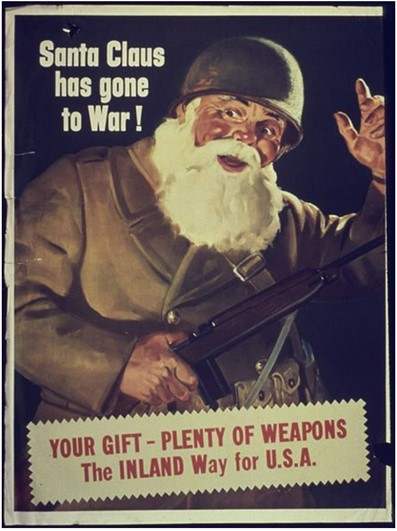

That isn’t to profess that his image didn’t occasionally revert to differing, and often bizarre, forms. In the Second World War, the US army offered a radical departure from the jolly, warm, red-suited Santa that had gained traction in the decades prior by presenting him in military uniform.

However, it was when Coca Cola commissioned illustrator Haddon Sundblom to develop advertising using Santa Claus, that the most recognisable figure to modern eyes was formulated. A warm, friendly, pleasantly plump, and human Santa enrobed in a soft red suit with white details formed the basis of the campaign.

Sundblom’s iconic Santa Claus debuted in 1931 in Coca Cola adverts that featured in the Saturday Evening Post. The beverages giant may not have invented Santa Claus, but its image of him holding a Coca Cola bottle was likely more widely disseminated than any other previous conception, and cemented it as the enduring depiction.

From Anderson’s gift-giving, deity-like figure to the US army’s militaristic, merry mercenary, it has been quite the evolution.

Merry Christmas from everyone at BlytheRay

X.com

X.com LinkedIn

LinkedIn